July 11-12, 2015

2nd Kyoto University-Inamori Foundation Joint Kyoto Prize Symposium

http://kuip.hq.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/archives/2015/about/

[Biological Sciences]

Svante Pääbo

Professor, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary

“Ancient DNA - from humble beginnings to high-quality genomes”

The vast majority of species and populations that ever lived on our planet are extinct. From a small fraction of these, tissues still exist either in museum collections or as archaeological and paleontological remains. Over the past 30 years, I have worked on developing and employing methods to retrieve DNA from such remains.

When an organism dies, its DNA is rapidly degraded by enzymatic processes and over time other chemical processes continue to damage the DNA. Therefore, ancient DNA molecules are present in small amounts and are degraded to small pieces that are often chemically modified. In addition, the contamination of old specimens or reagents with miniscule amounts of contemporary DNA can easily lead to erroneous results. Over the years, we have learned to overcome some of these problems and have been able to retrieve DNA sequences from Pleistocene organisms such as cave bears, mammoths and Neandertals. We have also shown that DNA can survive in other ancient remains such as coprolites and ancient corn cobs from early farmers. Our particular focus has been the reconstruction of DNA sequences from extinct hominins in order to illuminate human evolution and determine the genetic features that make us human.

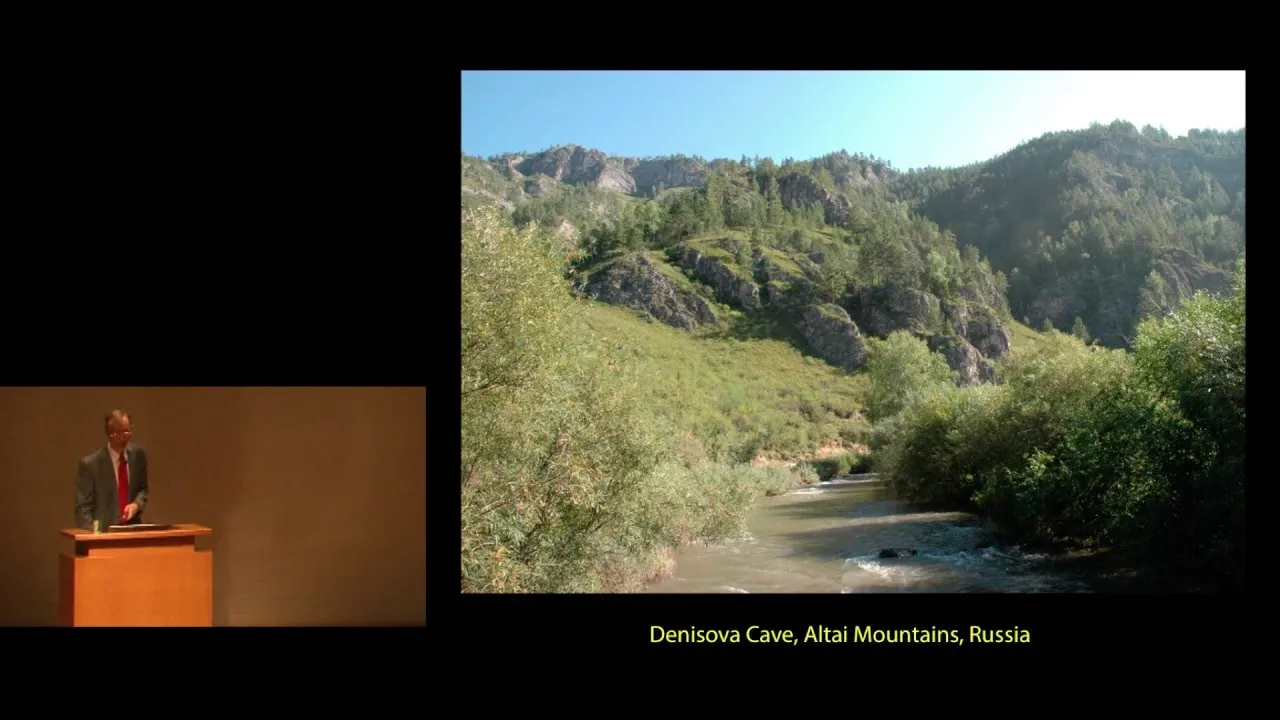

Our first draft version of the Neandertal genome in 2010, derived from three bones from Vindija Cave in Croatia, allowed us to show for the first time that Neandertals made a genetic contribution to humans living today. We subsequently completed a high-quality Neandertal genome and an additional high-quality genome from a tiny, unremarkable bone found in 2008 in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains. This genome turned out to be the first evidence for a hitherto unknown group of Asian hominins which were distantly related to Neandertals and are now called Denisovans.

Analyses of these genomes show that gene flow occurred among several different hominins in the late Pleistocene. In particular, Neandertals contributed about 2.0% of the genomes of people today living outside Africa while Denisovans contributed about 4.8% of the genomes of people living in Oceania and small amounts to people elsewhere in Asia. Work from several laboratories has shown that these genetic contributions have consequences today for the immune system, for lipid metabolism, for adaptation to life at high altitudes in the Himalayas, and for susceptibility to diseases such as diabetes. Further insights into our evolution are expected from our ongoing work to retrieve DNA from 400,000-year-old hominin fossils from Spain.

You can find the other lectures on Kyoto University OCW:

https://ocw.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/opencourse-en/134/video

この動画は、クリエイティブ・コモンズ・ライセンス“Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA)”が付与されています。 私的学習のほか非営利かつ教育的な目的において、適切なクレジット表記をおこなうことで、共有、転載、改変などの二次利用がおこなえます。 コンテンツを改変し新たに教材などを作成・公開する場合は、同じライセンスを継承する必要があります。 詳細は、クリエイティブ・コモンズのウェブサイトをご参照ください。

- 分野

- タグ